Chapter 2: Music Patrons: Blessing or Curse?

What worked for Bach that didn't for Mozart

In seventeenth-century Europe, a composer faced a stark choice. Accept patronage—the security of palace and cathedral, where survival was guaranteed but freedom negotiable. Or strike out independently—artistically free but economically exposed.

This wasn’t a philosophical debate. It was a daily reality that shaped what music got written, who owned it, and who could hear it.

Europe’s greatest musicians lived at the mercy of their patrons. Churches and aristocratic families sustained their work, but extracted a price: the music belonged to the benefactor, not the creator. The composer was, in effect, a highly skilled servant.

When the Statute of Anne introduced copyright law in the eighteenth century, Western music was deep in its Baroque period. The patron-composer relationship formed the industry’s infrastructure. Unlike today’s musicians, Baroque composers couldn’t simply release their work into the world. A patron’s money provided livelihood; a patron’s taste determined what could be composed; a patron’s permission controlled where it could be performed.

Two European masters navigated this system differently. Their choices reveal what’s actually at stake when we talk about creative freedom and ownership.

This is Chapter 2 of The Long Song: English to India. A recreation of my Tamil work in a series. New readers should start Chapter 1 for the full story. Subscribe to get new chapters in your mailbox.

Sebastian Bach: When Patronage Works

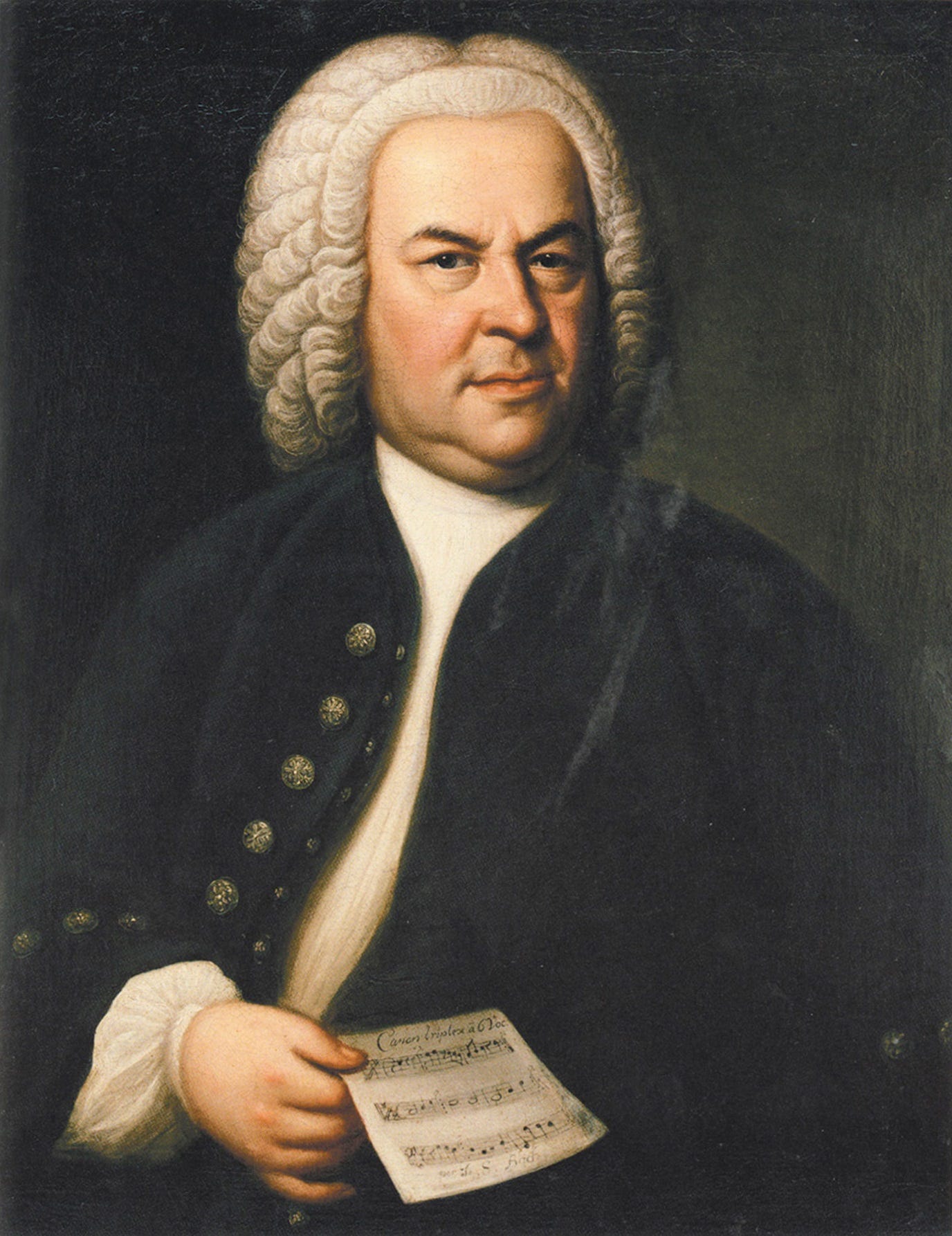

Among the Baroque giants—Bach, Handel, Vivaldi—Bach stands paramount.

Baroque music is dense, intricate, memorable. If you’ve ever heard classical music and a melody lodged itself in your memory, it was probably Baroque. That stickiness is characteristic of the form.

Bach mastered its most demanding technique: counterpoint. Multiple melodies playing simultaneously must interweave without collision, creating beauty through architectural precision. Bach’s counterpoint resembles a Kashmiri carpet—complex patterns that reveal themselves slowly, rewards for sustained attention.

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in 1685 into a modest German musical family. Both parents died before he turned ten. His older brother taught him music, which became his anchor in that emptiness. When a child loses everything, discovering art as consolation is fortune. Bach had that fortune. He pursued music with single-minded intensity, building the foundation for everything that followed.

Prince Leopold: The Patron as Friend

January 1716. A cold day. Sebastian Bach met Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen at a royal wedding. He didn’t know this encounter would redirect his life.

A year later, Leopold offered Bach the position of court musician at Cöthen. Bach accepted in August 1717 but couldn’t begin until December.

The delay? Bach served Duke Wilhelm Ernst, who reacted to Bach’s resignation with fury. Accusing Bach of improper procedure, Wilhelm imprisoned him. Bach spent a month in jail before beginning his new position. Some patrons viewed musicians not as employees but as property.

Leopold’s court transformed Bach’s work. His church duties were light, freeing him to compose prolifically. Many of Bach’s most significant works emerged during this period.

But this was more than employment. Leopold and Bach became friends. How close? Leopold served as godfather at Bach’s son’s baptism. (The child died young—Bach fathered twenty children, many dying in infancy, a common tragedy of the era.)

Leopold supported Bach’s experimentation. He was himself a musician and opera enthusiast who traveled Europe attending performances. He understood what Bach was attempting because he understood music from the inside.

But times changed. Military obligations to Prussia drained Leopold’s resources. Eventually, he couldn’t adequately compensate Bach.

In 1723, Bach made one of his hardest decisions. He left Cöthen to become music director at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig.

The friendship endured. Bach retained the honorary title “Court Musician” until Leopold’s death. In 1729, Bach traveled to Cöthen one final time—to compose music for Leopold’s funeral.

Their brief friendship enabled Bach to experiment, expand, and create lasting work. The Brandenburg Concertos—pieces that redefined orchestral music—came from this period. So did the Well-Tempered Clavier, which became the foundation of keyboard music education. In Brandenburg Concerto No. 6, Bach apparently wrote Leopold’s viola da gamba part to support rather than challenge—a subtle acknowledgment of their collaborative relationship.

Their story demonstrates something crucial: patronage could nurture genius when the patron understood art and respected the artist. When power served creativity rather than constrained it.

Half a century later, another musician rose to prominence. This Classical-era composer had studied counterpoint from Bach’s work as a young man.

His experience with patrons proved catastrophically different.

Mozart: The Cost of Freedom

Spring 1781. Vienna. In Archbishop Colloredo’s palace, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart stood with hands clasped behind his back, face rigid, staring at nothing.

He was about to lose his position. Or rather, he was about to force them to fire him.

Mozart worked as court musician to Archbishop Colloredo of Salzburg. “They grabbed me by the throat and threw me out,” Mozart later said. This moment fractured his life—the before and after of living on patronage versus living independently.

Mozart had grown up in royal courts. His father Leopold (no relation to Bach’s patron) took him on tours of European palaces. Young Mozart learned quickly: praise the benefactor, compose to specification, smile through it.

But as Mozart’s musicianship deepened, court service became intolerable. The Archbishop controlled not just Mozart’s employment but his music. Any composition created for the court couldn’t be performed elsewhere without permission. Mozart couldn’t experiment beyond the Archbishop’s taste. He was forbidden from holding concerts in Vienna’s halls.

The court position became a gilded cage. Mozart rebelled. When the conflict escalated, he did what European court musicians didn’t do: he quit.

The Freelance Experiment

His life became an adventure. He became Vienna’s first prominent freelance musician. Students from wealthy families sought lessons. He held concerts, created new music, staged operas without patron backing.

His opera Idomeneo exemplifies his ambition—its integration of music and drama was so innovative that music historians sometimes call it the world’s first film score, a technique that wouldn’t fully develop until cinema arrived over a century later. He’d won freedom to create groundbreaking work that would secure a permanent place in music history.

But freedom exacted its price.

Independence brought Mozart recognition and ruin simultaneously. Steady income vanished. He moved constantly, each home smaller than the last. He borrowed from friends. He wrote desperate letters to his father about hardship. His lifestyle and income diverged catastrophically.

His father couldn’t accept it. Mozart was advised to simplify his style, make his music more popular. Mozart refused. “I cannot compose music to satisfy everyone’s preferences.”

Even Emperor Joseph II’s court position—granted out of respect for Mozart’s talent—paid poorly.

Society viewed music as commodity, musicians as decorative court fixtures. Mozart fought this reality his entire life. Creative freedom on one side, economic survival on the other. The battle ended in 1791 at age thirty-five. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who gave the world timeless music, was buried in a common grave in Vienna.

Two Paths, Two Fates

Sebastian Bach raised twenty children—those who survived infancy. His composer positions provided stability: income to feed, house, and educate them.

Mozart’s family of six struggled through unstable earnings. His widow barely afforded his funeral expenses.

From Mozart’s perspective, patronage meant imprisonment. Only independence enabled the music he needed to create. He paid everything for this belief. He left behind immortal work and died in poverty.

These two lives pose a question that still haunts artists: Must you choose between freedom and survival? Between creating what matters and maintaining stability? Between artistic integrity and economic security?

For most of history, the answer seemed to be yes.

But Bach’s youngest son discovered something different. Christian Bach managed to live independently, create freely, and die comfortably—without patron control, without Mozart’s poverty.

The reason? London.

The city that burned to the ground in 1666 had rebuilt itself into something unprecedented: a place where artists could reach audiences directly, where music became a business rather than a gift from patrons to the privileged few.

London was inventing the creator economy.

This is Chapter 2 of The Long Song: English to India. A recreation of my Tamil work in a series. New readers should start Chapter 1 for the full story. Subscribe to get new chapters in your mailbox.