I wasn’t looking for Nina Protocol. I stumbled into it because someone on Reddit was complaining about the label Numero Group leaving Bandcamp. “Why would they abandon a platform that works?” the commenter asked. I had the same question. So I went to investigate.

Nina Protocol is a music platform that stores songs on blockchain—think of it like carving your music into stone tablets instead of writing it in notebooks. The notebooks (Bandcamp, SoundCloud) can burn or get thrown away when companies sell or shut down. The stone tablets are supposed to last forever, scattered across thousands of computers instead of sitting on one company’s server that can get unplugged. Whether they actually will is another question.

But first, I need to tell you about the electronic musicians on Bandcamp.

The Warmth

They follow me. Electronic producers, ambient artists, experimental musicians. We don’t discuss music. We have nothing in common aesthetically. I’m not making what they’re making, they’re not making what I’m making.

But they follow. Across platforms. I’m on Bandcamp, they’re there. I post somewhere on Reddit, they show up. It’s not about my music. It’s something else.

And here’s the strange part: they’re the warmest musical community I’ve ever encountered. Not competitive. Not cold. Not performing prestige. Just... present. Ready to connect. Ready to help if asked.

I didn’t understand it until I started researching Nina Protocol.

The Paint Store

There’s a paint store in my town run by a Sri Lankan Tamil man. I’ve heard he provides refuge; his own people who can’t find a job end up there, doing painting labor. He’s successful, well-known. But the refuge remains.

I thought about him when I saw a music tech company’s promotional video featuring an electronic artist I recognized. Big spotlight, corporate endorsement, sleek product demos. Success. Visibility. Legitimacy.

But I won’t be surprised if this artist still follows hundreds of bedroom producers on Bandcamp, still engages with Nina Protocol conversations, still a part of the network, despite the spotlight.

The paint store owner could just be a successful businessman. The artist could just be a successful producer. But something stays. Some kinship hidden in the heart. Some memory that success doesn’t erase.

Why?

What I Found on Nina

Nina Protocol is all electronic music. Experimental, leftfield, underground. No Beatport commercial EDM. No top 40. Just... refugees.

That’s what it felt like browsing it. Artists with no institutional backing, no major label support, no concert hall bookings. Making music in bedrooms, basements, home studios. Uploading to platforms that might not exist in five years.

It reminded me of the Sri Lankan refugee camps I’ve glimpsed near my hometown. Not in a political way. I’m not making deep comparisons. Just... the feeling. Temporary shelters. Communities forming in displacement. People helping each other survive in spaces that weren’t built for permanence.

Electronic musicians have been doing this for decades.

The Pattern

I started digging into the history of platforms I witnessed. What I found was startling.

MP3.com : One of the first platforms where independent electronic musicians could distribute music. Lawsuits killed it. Music lost.

MySpace: The golden era. Dubstep, grime, electro-house, indie electronic and entire genres born there. MySpace democratized electronic music distribution. Then Facebook won the social media war. MySpace declined. A server migration catastrophically failed and deleted an estimated 50 million songs just gone. Years of work. Entire scenes. Erased.

SoundCloud : After MySpace lost its glory, everyone moved here. Vaporwave, future bass, lo-fi house, SoundCloud rap. Then: copyright strikes, near-bankruptcy with mass layoffs, endless monetization crises. It still exists, figuring out its own ground in a new reality.

Bandcamp : The refuge after SoundCloud’s uncertainty. Artist-friendly. Fair revenue split. Community-focused. Then: Sold to Epic Games. Sold again to Songtradr. Approximately 50% of staff laid off. Union not recognized. Editorial team gutted.

And now: Nina Protocol: Web3, blockchain, promises of permanence. Launched in 2021, relaunched with a simplified interface in 2023. Artists keep 100% of primary sales. Music stored on Arweave. It is permanent storage on blockchain—the stone tablets as we discussed earlier.

Web3 is the idea of a decentralized internet where users own their data and content instead of corporations controlling everything. Right now, platforms like Bandcamp or SoundCloud are landlords, they own the building, you rent space, and if they sell or shut down, you lose everything.

Web3 promises to make you the owner, your music lives on a distributed network (blockchain) that no single company controls. You hold the deed, not a rental agreement.

Whether that promise actually works is still being tested.

In August 2025, Numero Group announced via Instagram they were moving their catalog to Nina Protocol. Not abandoning Bandcamp entirely, but diversifying.

But one can see the pattern. Every platform promises stability. Every platform eventually fails or changes or gets sold. And electronic musicians pack up and migrate again.

This goes back further than digital platforms. In the 1940s and 50s, experimental composers needed access to radio studios just to make electronic music. The institutions controlled the means of production.

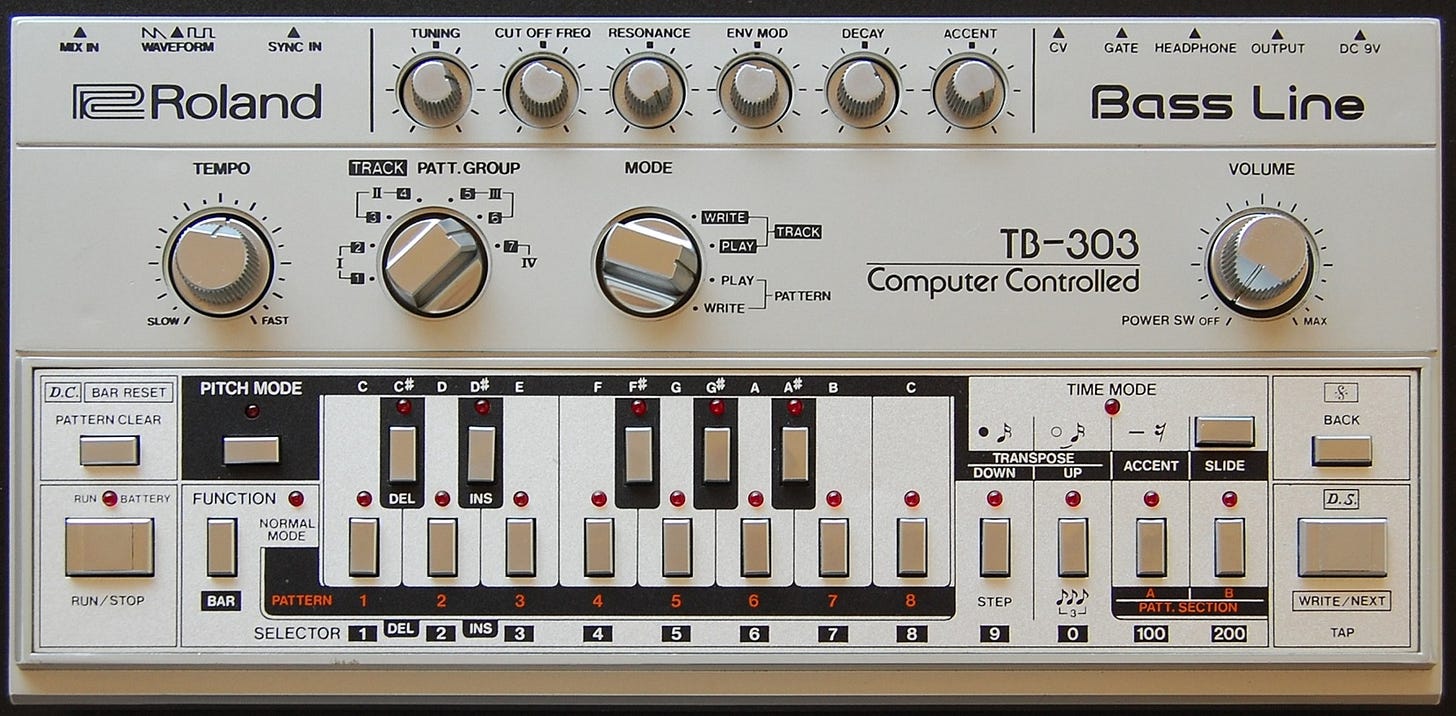

In the 1980s, Chicago house and Detroit techno producers bought discontinued Roland equipment, the TB-303 bass synthesizer, the TR-808 drum machine because they were commercial failures. Roland had discontinued them. The producers made art from corporate waste.

Always displaced. Always migrating. Always building temporary homes.

Why “Underground”?

I used to think “underground” meant the sound. Experimental, uncommercial, weird.

But I think it means something else now.

Underground means beneath institutions. By choice? By exclusion? Or more nuanced?

But what I see is the Underground that’s temporary like literal resistance movements constantly relocating as a defense strategy. No permanent headquarters. Always moving.

Refugee status as a permanent condition? A survival strategy? Or something else entirely?

The Bandcamp Shift

Here’s what I think Numero Group smelled.

Bandcamp started as anti-algorithmic. Fan-driven discovery. Artist control. Community recommendations. No Spotify-style AI curators deciding what you hear.

Then, it launched “Bandcamp Clubs.” Curated subscriptions. A connoisseur picks music for you. Thirteen dollars a month.

It’s not an algorithm—it’s human algorithms. Gatekeepers with better branding.

The warmth was being replaced with editorial control. The community was becoming an institution.

Numero Group has institutional memory. They’ve watched platforms die before. They smelled what happens next: Bandcamp stops being a refuge and starts being a business. The community leaves. The pattern repeats.

So Numero Group went to Nina. Not because Nina is guaranteed to survive. But because you don’t put all your eggs in one basket when you’re either a refugee or a rebellion.

The Brotherhood

I think I finally understand why electronic musicians follow me on Bandcamp.

It’s not about my music. It’s not about shared taste or aesthetic alignment.

It’s about the network.

When MySpace had a crisis, people with strong ties, close collaborators, deep friendships that often lost contact entirely. People with weak ties—hundreds of follows but minimal interaction—found each other on the next platform. Someone remembered. Someone reconnected.

Electronic musicians have been building this resilient network for decades. Following broadly. Staying present. Not because they love everyone’s music. Because when the next platform dies, it will and someone will be there when they arrive at the next one.

They’re adding me to that network. Not because they listen to my work. Because I’m present in digital spaces. Because maybe I understand precarity even if I haven’t fully experienced it yet. Because maybe someday I’ll be a refugee too.

The warmth isn’t friendship. It’s mutual aid as insurance policy. I help you now, you help me later.

Following = “I see you. You exist. When this platform dies, I’ll remember you were here.”

That’s the brotherhood. Not deep ties. Not collaboration. Just... distributed presence across platforms. The survival network of the displaced.

The Hidden Kinship

The music tech company artist still following bedroom producers. The paint store owner still hiring his people who can’t find work. Electronic musicians still following me even though we make completely different music.

Success doesn’t erase the memory of being both refugee and rebel.

The paint store owner remembers what it’s like to need refuge. The artist remembers the underground even with the corporate spotlight. The electronic musicians remember or know it could happen to them.

And they maintain the network because they know: platforms die, institutions crumble, and when that happens, the only thing that survives is the kinship you built when you didn’t need it yet.

Why It Keeps Happening

I keep asking myself: why does this pattern repeat? Why can’t electronic music find stable infrastructure?

I have theories, not answers.

Maybe it’s capitalism. Platforms need growth. Growth requires monetization. Monetization requires gatekeepers, algorithms or curators. Gatekeepers kill the community warmth. The community leaves. A new platform emerges. Repeat.

Maybe it’s the nature of digital spaces. Physical institutions last centuries. Concert halls from the 1800s still host music. But digital platforms? Five to ten years, then corporate acquisition or death.

Maybe it’s also the law. Copyright, platform liability, artist rights. The legal framework keeps chasing technology, always a few steps behind, leaving artists perpetually vulnerable to whoever controls the infrastructure.

Maybe displacement is just the condition. Not a problem to solve. Just... the reality. And maybe the warmth, the mutual aid, the resilient networks, maybe those only exist because of the displacement.

Nina and What Comes After

Is Nina Protocol different? Will blockchain actually create “infrastructure for the next 50 years of music” like they claim?

I don’t know.

The technology is interesting. Music stored permanently. Artists keep 100% of primary sales.

But I’ve read the critiques too. The music is publicly downloadable by anyone who knows where to look on the blockchain. The permanence cuts both ways. There was drama in 2023 about Arweave potentially forking, splitting into competing versions, and whether that could delete all existing data. Nina uses third-party services that could fail. The crypto wallet system is confusing for many artists.

Solana is the blockchain Nina uses for transactions. Think of it as the payment queue.

When you buy music on Nina, Solana processes that transaction quickly (like a fast checkout) instead of the slow, expensive processing that happens on older blockchains like Bitcoin or Ethereum.

It’s separate from Arweave (the permanent storage/stone tablets). Solana handles the buying and selling, Arweave handles the keeping forever. Two different jobs

I think the question isn’t whether Nina will survive.

The question is: what comes after Nina?

Because something always does. The refugees and rebels will move again. They always have.

What I Learned

That Reddit commenter asking “Why would Numero Group leave Bandcamp?” had institutional thinking. “Why leave what works?”

But Numero Group has refugee thinking. Eighty years of watching platforms rise and fall. They don’t trust any single platform to last. They build networks everywhere. They maintain kinship with the displaced even when they’re successful enough not to need it.

The electronic musicians who follow me on Bandcamp? They’re living refugee and rebel thinking every day. The follow button is their paint store.

And maybe that’s what “underground” really means. Not hidden. Not secret. Not even uncommercial.

Perpetually displaced. Always building temporary shelter while knowing it won’t last.

And maybe that’s not a problem. Maybe that’s just the condition.

If you would like to support my work, I have my music and PDF companions on Bandcamp and my ko-fi shop. Why two platforms? I can smell something Numero Group might’ve had.