The New London

The year 1666. A London bakery. Someone left the oven burning overnight. The embers sparked. Wind caught. Fire spread.

Five days later, when the Great Fire finally burned out, London lay in ruins. Residents became refugees in their own city.

The fire consumed St. Paul’s Cathedral and countless churches. Concert halls vanished. Musical scores—irreplaceable manuscripts—turned to ash.

Catastrophe forced reinvention. Building codes, fire regulations, insurance systems—all were restructured. London’s streets, churches, and major buildings rose anew. St. Paul’s Cathedral was magnificently rebuilt. The Monument still stands where the fire started on Pudding Lane, commemorating the phoenix-resurrection of a city.

The Baroque and Neoclassical buildings constructed during reconstruction later drew tourists from across Europe. By the eighteenth century, London had become one of the world’s wealthiest cities. Atlantic trade—particularly in sugar, tobacco, and enslaved people from colonial territories—generated massive wealth.

This new prosperity created a new class: wealthy merchants who valued philosophy, art, and music. They had money but no aristocratic pedigree. They needed culture to establish their social position.

Artists, writers, composers, and philosophers converged on London. Opera, concerts, and exhibitions proliferated. George Frideric Handel spent most of his life there. Voltaire and Rousseau worked from London.

From total destruction, London rebuilt itself into Europe’s cultural and economic powerhouse—a global leader in commerce, science, and the arts.

This was the London that welcomed Christian Bach.

Christian Bach in London

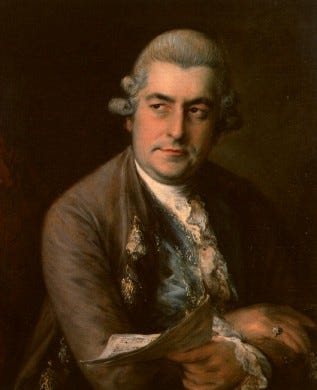

Autumn evening, 1762. A carriage rattles through London streets. Inside sits twenty-seven-year-old Christian Bach, arrived from Italy. Churches and theaters glow golden in fading light. He can barely contain his excitement about what this city might offer.

The next day, performing on stage, Bach studies the London audience. These aren’t Italian patrons expecting flattery. Their eyes show different hunger—artistic thirst, genuine enthusiasm for innovation.

Before the applause ends, Bach decides: his future is here.

His subsequent opera productions captivated London. He blended Italian musical sophistication with English theatrical narrative—innovation that delighted audiences hungry for novelty. London’s appetite for new forms drove Bach to continuous experimentation.

His childhood friend Carl Friedrich Abel was already working in London as a composer. Both had studied under Sebastian Bach. They decided to collaborate, holding concerts together.

Being a great composer’s son is like growing in a giant’s shadow—the protection is real, but so is the darkness. Music history knows one “Bach”: Sebastian. Yet Christian carved his own identity through talent and entrepreneurship, earning the distinction “The London Bach.”

Bach and Abel proved not just musicians but businessmen. Their success built on London’s particular history—innovations created by two pioneers who had reimagined what concerts could be.

This London was built on changes that began a century earlier.

Paid Concerts—John Banister

December 30, 1672. Evening. A small London tavern in Whitefriars. Dim lamps, coffee cups clinking, loud conversation.

John Banister, accomplished violinist and composer, prepares for something unprecedented: making concert music—previously exclusive to royalty and aristocracy—accessible to anyone who could pay.

Word has spread. Music lovers gather. Writers, clockmakers, small tradespeople. Different professions, shared passion. Each carries coins, ready to exchange hard-earned wages for something they’d never been allowed to experience.

London’s first paid public concert.

The musicians Banister selected perform. The music of masters reaches ears that have never heard such work live. When it ends, the room erupts—applause, excited conversation, people sharing an experience they’ll never forget.

This had never happened before in London. Before this moment, a common man couldn’t pay to hear music he or she desired.

The concerts continued. Anyone who paid was admitted. John Banister showed musicians something revolutionary: an innovative way to reach people beyond palaces and churches.

Later, another musician took this idea further.

Subscription Concerts—Thomas Britton

Thomas Britton sold coal in London’s Clerkenwell district. He possessed literary and artistic interests. And unquenchable musical passion.

Above his coal warehouse was an attic. Starting in 1678, he held concerts there, making excellent musical compositions accessible to ordinary people.

Initially: free admission. Anyone could enter. Later: a modest subscription fee. Ten shillings annually for weekly concerts. Ten shillings—an amount a working person could afford without hardship.

Britton’s subscription system democratized access to great music on a scale London had never seen.

That coal-dust-filled attic became sanctuary for ordinary citizens thirsting for art. Britton’s innovation—subscription concerts—became the model many London artists adopted. It showed musicians they could earn sustainable income directly from audiences, not patrons.

This was precisely how Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel structured their London careers.

London: The Laboratory

Eighteenth-century London became a convergence point for diverse cultures and intellectual traditions. The music world’s transformation reflected in its concert halls.

Crowded streets where different classes and cultures mixed. Restaurants where diverse backgrounds sat shoulder to shoulder. Pubs where philosophy was debated over drinks. Street performers offering new sounds to passersby. London incubated cultural revolution.

Economic prosperity created new social structures. A wealthy merchant class emerged that valued philosophy, art, and music. This drew artists from across Europe. Concerts moved from castles and churches into public halls.

Thomas Britton’s subscription model spread. Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel became its most successful practitioners.

The voice for change echoed throughout London. Growth in creative freedom, cultural exchange, and philosophical discourse generated new opportunities and new markets.

And new legal questions.

London became the testing ground for copyright law’s development. Historically significant cases debated in its courts would reshape how society understood creative ownership.

Among these cases, one involving Christian Bach would prove particularly significant. It was a landmark too.

This is Chapter 3 of The Long Song: English to India. A recreation of my Tamil work in a series. New readers should start Chapter 1 for the full story. Subscribe to get new chapters in your mailbox.