In Tamil Nadu, the state I live in, a section of people started debating whether Mahakavi Bharathi is a progressive poet or not. They divide into two groups. The issue roots in Bharathi’s caste.

For readers unfamiliar: Subramania Bharathi (1882–1921), is our Whitman-meets-Yeats. Democratic fire with mystical intensity. He wrote fierce songs against British colonialism, against caste discrimination, for women’s liberation. They are radical even by today’s standards. His poems remain sung at protests, weddings, school assemblies. He died young, poor, struck by an elephant at a temple. The kind of death that makes legends.

Caste is the crux of Tamil Nadu politics, if not of entire India. From creating narratives to appointing candidates, everything tied with caste calculus.

I recall days when I engaged in debates like these, believing facts and logical arguments would change minds. I’d compile quotes, context, historical evidence. I’d type long responses with citations. I believed in the power of correct information.

Now I watch them continue debates, passionate about positions that will reverse in next election cycle. I sit quiet at tables where friends parse Bharathi’s verse. I feel lonely.

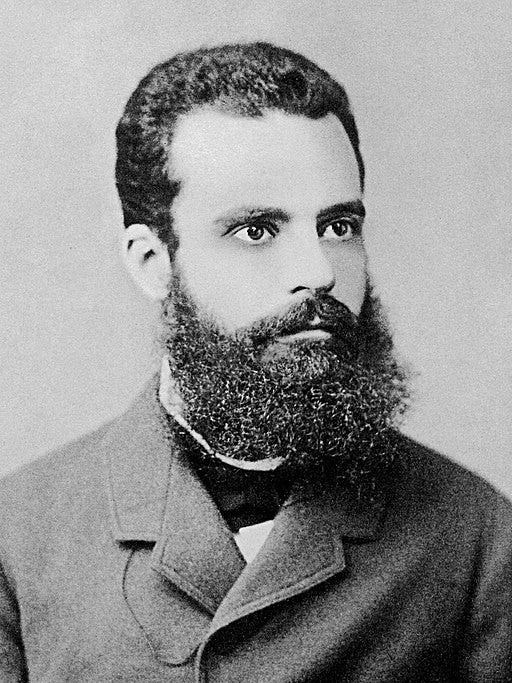

Vilfredo Pareto, the same one behind the 80/20 rule, developed something less famous but more devastating. His theory argues that human action springs from non-logical sources. Residues are deep drives: instincts for preservation, group belonging, maintaining what exists. Derivations are the elaborate justifications we construct afterward. Logic isn’t the engine. It’s the paint job. Pareto saw that humans find relief in believing themselves rational.

Watch the Bharathi debate with Pareto’s lens. The poems haven’t changed. Bharathi hasn’t written anything new recently, being dead since 1921. But suddenly he needs re-evaluation. Why now? Because someone needs him problematic for today’s political formation. Someone else needs him progressive for theirs.

The same verse that was revolutionary last decade becomes casteist this decade. Not because we discovered new meaning. Because we need new ammunition.

The comedy is watching people cite the same poems to prove opposite points. Like Bharathi wrote in quantum states, simultaneously progressive and regressive until political observation collapses him into one.

Pareto's theory was funny when I read it at thirty. Now it doesn’t sound funny. He was documenting tragedy as sociology.

The loneliness isn’t from disagreement. It’s from seeing the mechanism. Like watching a magic show from backstage. You see the strings, the trapdoors, the assistant crouched in the “empty” box. You can’t unsee it. You also can’t participate anymore. Not honestly.

Sometimes they ask why I don’t engage. “You used to have such strong opinions,” they say. I do. The opinion is that we’re all performing derivations while our residues run the show. But saying that out loud is social suicide. So, I just smile. Another derivation to hide my residue: exhaustion with the whole performance.

The cost of knowing what Pareto knew: you become audience to a play where everyone else is cast and script. You lose the comfort of believing in belief itself. Every passionate argument sounds like sophisticated noise.

But you still show up. Still sit at the tables. Still perform enough derivations to stay connected. Because the residue for belonging is stronger than the knowledge that belonging requires performed blindness.

Pareto knew something. Knowing what he knew doesn’t set you free. It just makes you conscious of the cage while you remain inside it.

Excellent piece. Once you see it, sadly people follow narratives every election cycle of “I’ll fix this”. You might enjoy this piece…https://kevinguiney.substack.com/p/the-unfinished-question-on-democracy