Chapter 1: An Elephant in Sugarcane Field

The Story of How the World's First Copyright Law Was Born

The Precious Book

This is Chapter 1 of The Long Song: English to India. A recreation of my Tamil work in a series. New readers should start here. Subscribe to get new chapters in your mailbox.

Fourteenth-century England. The village of Woolpit.

Sir Edmund’s manor house. Evening sun fell across the grey stone walls. In the distance, wool bales were being loaded onto carts, and sheep returned to their pens.

In the courtyard, Edmund held a book, beautifully crafted with a calfskin cover. Clergy from Woolpit village gathered around, their eyes filled with wonder.

“This is my family treasure,” said Edmund, his eyes wide with reverence. “My father spent a fortune to have it written by skilled scribes in London. I wish to use it in our church service this coming Sunday, on my father’s memorial day.”

“You must handle it with the utmost care during the service,” he said. Everyone nodded reverently, knowing this was the only book for miles around.

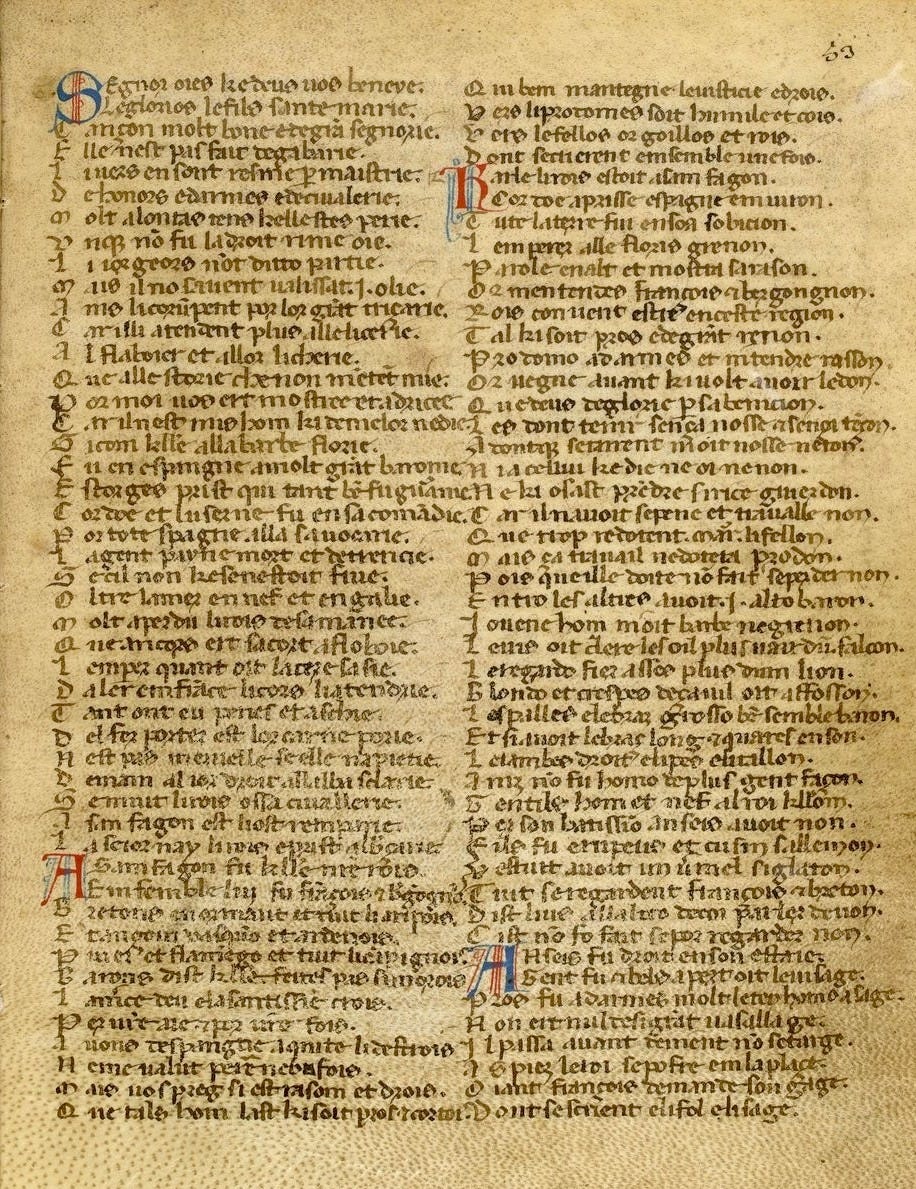

This was before the printing press existed. Creating a book was no ordinary matter. Though Sir Edmund’s family wasn’t among England’s highest nobility, a book represented a generational dream even for them. Common people could not even dream of books—they could only hear clergy read from them during church worship. That was their only connection to books.

Professionals called “scribes” would write books by hand, copying them one word at a time. Finding a scribe with excellent penmanship and literacy required significant expense. A well-written book with decorative covers could cost a common person their entire life’s wages.

Writing a book could take weeks, months, or even years. Only the elite—royal courts, churches, and universities—could establish libraries. Reading a rare book needed connections: to the royal court, to university libraries, to wealthy collectors.

But something was Sir Edmund and the clergy couldn’t imagine was taking shape in a corner of Germany.

The First Press

The year 1453. The city of Mainz, Germany.

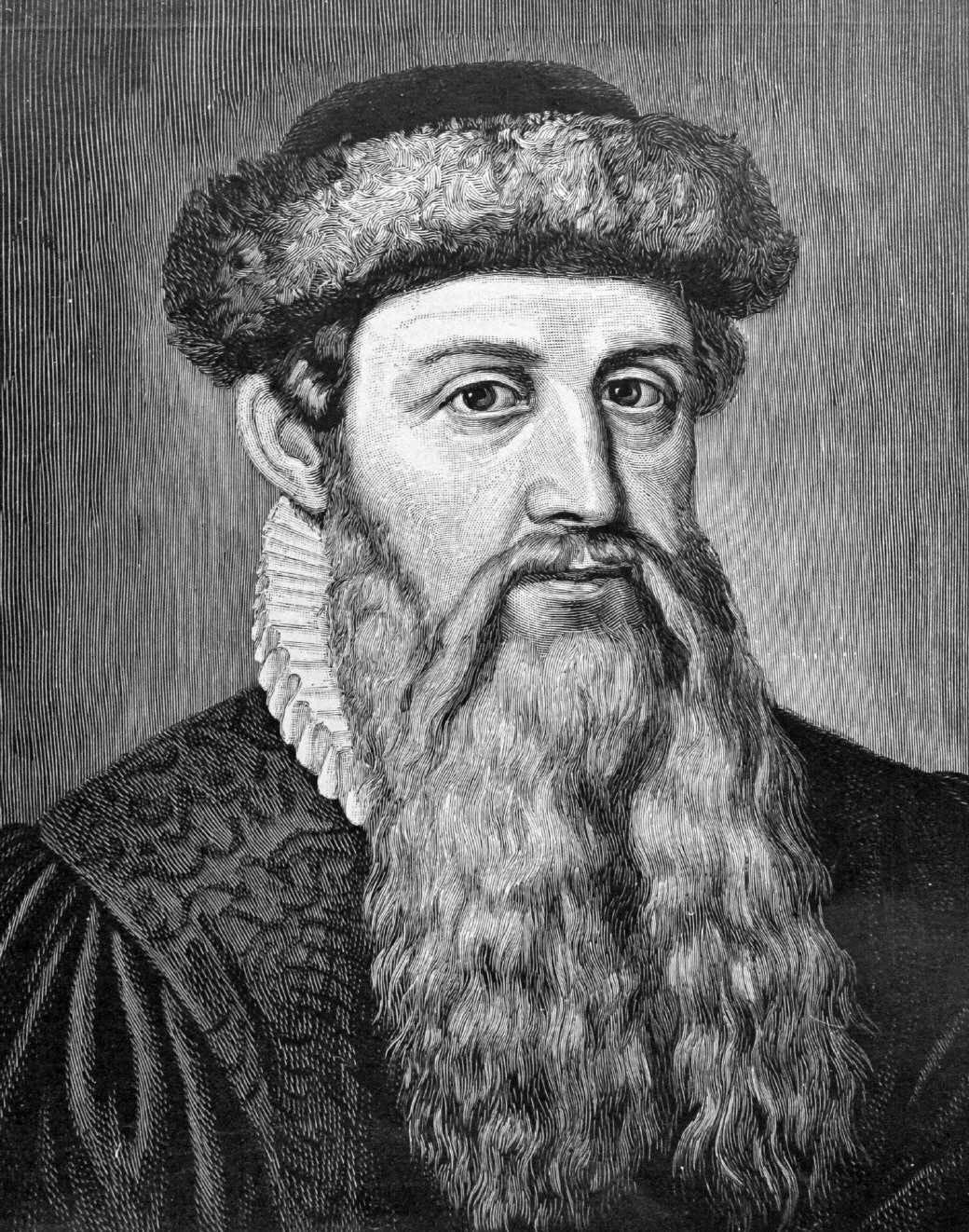

In his workshop, Johannes Gutenberg wiped sweat from his forehead and stared at the stubborn contraption before him. He examined the ruined paper in his hand, bleeding ink.

He had been struggling for months to make this machine work. His experience as a goldsmith had helped him select the right metal for the moving parts of the press.

He threw away the crumpled, ink-stained paper and began dismantling the machine to fix it. Great effort, hardship, and expenditure. The price Gutenberg paid for his dream was high.

Finally, in 1454, Gutenberg’s printing press was ready. What he chose to print first was the Bible—one hundred and eighty copies in total. Some were made with paper, others with vellum. Each was unique: different covers, different decorations, different experimental touches. Of these, forty-nine Bibles exist today, treasured in museums and private collections.

This first printing press with “movable type” that Gutenberg created soon spread to other European countries. Many learned the trade, including an English merchant.

England’s First Printed Book

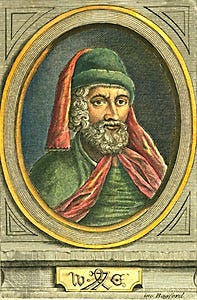

Cold sea wind filled the sails as the ship departed London’s port. William Caxton stood on deck, watching the city gradually recede and disappear behind him. The ship was heading toward Bruges in Belgium.

Caxton had been an assistant to Robert Large, a London cloth merchant. After Large’s death, he was traveling to Bruges seeking new opportunities. His plan was the luxury garment trade. With its prosperity and cultural richness, Bruges seemed far more suitable than London, which was full of small wool merchants.

When they reached Bruges, a new world welcomed Caxton. The harbor was full of merchant ships flying flags from many nations. Unlike London’s muddy lanes, Bruges had stone-paved streets kept spotlessly clean. Barges glided through the city’s network of canals.

Over thirty years, Caxton became one of Bruges’ leading merchants. During this time, he developed a passion for literature, particularly translation. He began translating books from European languages into English—exhausting work.

“My pen nib wore out. My hands grew weary from endless writing. My eyes dimmed...” Caxton later recounted. This led him to learn the printing trade.

After decades in the textile trade, Caxton made a bold decision. With a technical expert’s help, he established a printing house in Bruges. The following year, he published the first printed book in English: The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, translated from French, in 1475.

Caxton’s press gained fame in Bruges. But his heart kept turning back toward London, where he was born and raised.

One day, Caxton stood on a ship departing Bruges and approaching London. Ahead, the city appeared on the horizon, growing larger with each passing moment. When the boxes of metal type and ink bottles were unloaded at London’s port that day, the city prepared to write a new chapter in its literary history.

England’s First Press

Caxton sat in his printing house. Outside, the bells of Westminster Abbey rang across the city. In his hands was an old manuscript—a collection of stories written a century earlier by Geoffrey Chaucer.

The Canterbury Tales, printed in Caxton’s Westminster press, secured an indelible place in English literary history.

Meanwhile, the handwritten prayer book from Lord Edmund’s manor remained in the care of his heirs. It had become a rare art object, a relic of a vanished world. In England now, books were no longer rare commodities.

Print and the Panic! (1476-1557)

Following Caxton’s press, printing houses sprang up across London. Every street filled with the clatter of printing machines. Books multiplied. A new industry took flight.

London’s markets flooded with cheap, error-ridden books. Protestant pamphlets attacking the Catholic Church were printed and distributed among the people. Pamphlets criticizing the royal family circulated throughout the city.

Writers’ works became books without their permission. Anyone could print anything. Concerns grew. Calls for regulation grew louder.

Petitions reached Queen Mary I demanding regulation of the publishing industry. Leading the charge were members of an organization called the Stationers’ Company.

In 1403, London’s book tradesmen—writers, scribes, sellers, binders, paper makers—had formed an association: the Stationers’ Company. In those days, such associations regulated each trade. They were called guilds.

On May 4, 1557, responding to concerns about uncontrolled printing, Queen Mary granted the Stationers’ Company authority to regulate the entire publishing industry.

The Stationers’ Company used every means to control the printing trade. In the years that followed, England’s printing industry became like Gutenberg’s crumpled, ink-stained paper—discarded.

Crumpled and Discarded Papers

On a noisy London street, Jacob walked through the crowd carrying newly printed pamphlets that still smelled of ink. He worked at a printing house nearby. As he approached, the sight shocked him. He stopped and watched from a distance.

The printing house doors had been broken down. Papers lay scattered inside. Shelves had been ransacked. His employer lay on the floor in a pool of blood. Standing over him were men from the Stationers’ Company.

“The pamphlets you printed are against the queen’s rule!” an officer shouted. From his hiding spot, Jacob let the pamphlets slip from his hands. His palms were slick with sweat.

In the following weeks, Jacob learned his employer had been secretly publishing Protestant writings.

Jacob now worked at a different printing house, one registered with the Stationers’ Company. Every manuscript had to be submitted for approval. The Company censored them. Works containing political, social, or religious sensitivities were banned. Manuscripts were destroyed.

Jacob worked hard at this printing house. Every day as he set type for approved publications, he felt eyes watching from behind.

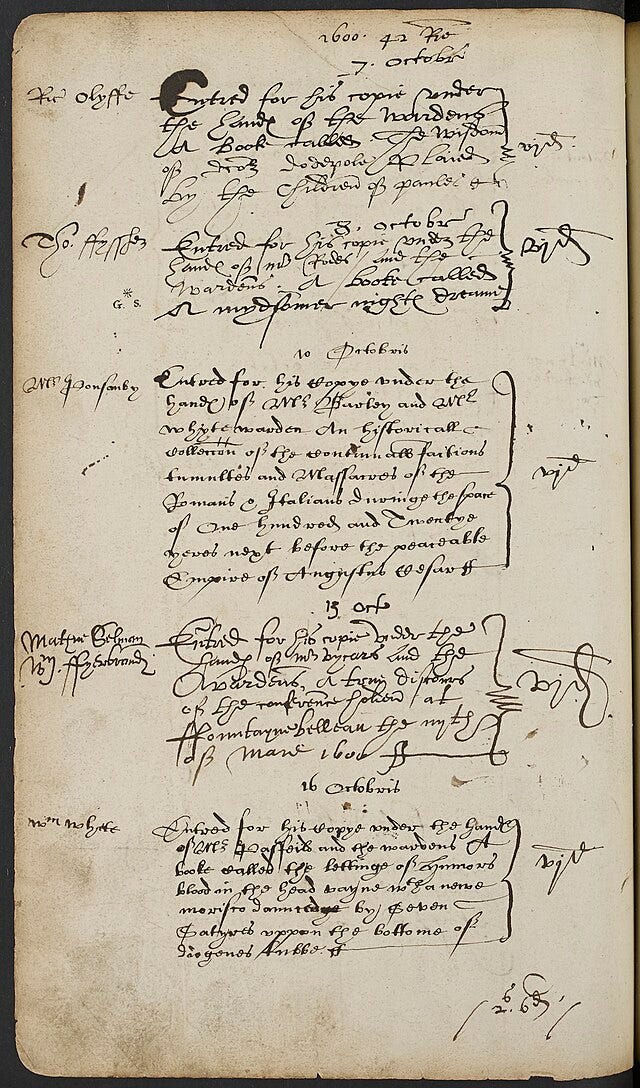

Under the new system, writers had to submit applications to the Stationers’ Company before publishing. Manuscripts were censored. Paper, ink, and all materials had to meet Company standards.

The Stationers’ Company had authority to confiscate and destroy unauthorized publications. Printers who defied them were punished.

John Wolfe, for example, was arrested twice and imprisoned. His crime? Publishing books that violated Company regulations.

Yet the Stationers’ Company considers itself history’s first copyright organization.

The World’s First Copyright Law - The Statute of Anne, 1710

Amid England’s political upheavals, the Stationers’ Company maintained its authority. Sometimes their power waxed, sometimes it waned. But their importance never faded.

Then in 1694, when the law granting the Company its authority expired, Parliament refused to renew it. The Stationers’ Company’s authority came to an end.

But immediately, old problems resurfaced. Books were published without controls. Publishers printed authors’ works without permission.

These cheap pirated editions sold in vast quantities. Publishers grew wealthy. Writers languished in poverty.

Once again, calls for regulation grew louder. A law was needed to prohibit unauthorized publishing. The idea of copyright law gained widespread support.

The Stationers’ Company saw an opportunity to regain its lost importance. They joined the writers petitioning Parliament for copyright protection. Together, they asked for copyright law without time limits.

Parliament refused perpetual copyright but agreed to create copyright law with time limits.

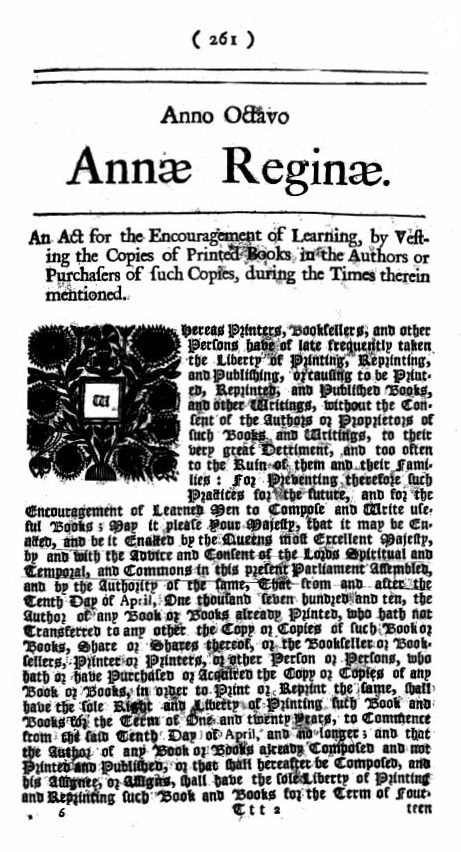

The law passed in 1710 became known as the Statute of Anne—the world’s first copyright law.

Under the new law, writers registered their works with institutions like Oxford University. The Stationers’ Company transformed into a copyright registry.

Copyright lasted fourteen years. If the creator still lived, it could be renewed for another fourteen years. After that, the work entered the public domain. The law also allowed copyright transfer between parties.

New business practices emerged in publishing: copyright registration, licensing agreements, rights transfers. The fundamentals of today’s creative industries took shape.

Lord Edmund’s handwritten prayer book, still in his heirs’ possession, had become a museum piece.

The Pattern Repeats...

The printing press published not only books but also musical notation.

Just as pirated books flooded the market, so did unauthorized sheet music. Composers, like writers, suffered from piracy.

But the Statute of Anne covered only written works. Musicians had to turn to the courts for protection.

Musical notation cases posed unique challenges. What if someone printed sheet music without permission—not as a book, but as a single page? How did copyright apply?

New questions arrived at London’s courtroom doors.

The printing press had disrupted everything in its path. Tamil people would call this “an elephant in a sugarcane field”—something that destroys everything as it moves forward. Each subsequent invention upended the creative industries in similar fashion. Each time, humanity grappled with the disruption and adapted.

This pattern repeats throughout history. By understanding it, can we better face the challenges before us today?

This is Chapter 1 of The Long Song: English to India. A recreation of my Tamil work in a series. New readers should start here. Subscribe to get new chapters in your mailbox.